lxml and Requests¶

lxml is a pretty extensive library written for parsingXML and HTML documents very quickly, even handling messed up tags in theprocess. We will also be using theRequests module instead of thealready built-in urllib2 module due to improvements in speed and readability.You can easily install both using pipinstalllxml andpipinstallrequests.

LXML is a lightweight HTML parser even the most popular web scraping framework (Scrapy) is built on the top of LXML, BeautifulSoup is a little bit overloaded with the number of functions exposed to us, it has more functions to use, yes that’s right! However in Web Scraping most of the time we use XPath and CSS Selectors to navigate.

Lxml Website Scraping

Let’s start with the imports:

- Pandas web scraping Install modules. It needs the modules lxml. $ pip install lxml html5lib beautifulsoup4: pands.readhtml You can use the function readhtml.

- #webscraping #python🔥This web scraping crash course is only a demo of my new course on Udemy🔥.If you want to get the full 4.5 hours course you can use the.

- LXML is a lightweight HTML parser even the most popular web scraping framework (Scrapy) is built on the top of LXML, BeautifulSoup is a little bit overloaded with the number of functions exposed to us, it has more functions to use, yes that’s right! However in Web Scraping most of the time we use XPath and CSS Selectors to navigate and select what to scrape from the HTML web page (tree) so there is no need to.

Next we will use requests.get to retrieve the web page with our data,parse it using the html module, and save the results in tree:

(We need to use page.content rather than page.text becausehtml.fromstring implicitly expects bytes as input.)

tree now contains the whole HTML file in a nice tree structure whichwe can go over two different ways: XPath and CSSSelect. In this example, wewill focus on the former.

XPath is a way of locating information in structured documents such asHTML or XML documents. A good introduction to XPath is onW3Schools .

There are also various tools for obtaining the XPath of elements such asFireBug for Firefox or the Chrome Inspector. If you’re using Chrome, youcan right click an element, choose ‘Inspect element’, highlight the code,right click again, and choose ‘Copy XPath’.

After a quick analysis, we see that in our page the data is contained intwo elements – one is a div with title ‘buyer-name’ and the other is aspan with class ‘item-price’:

Knowing this we can create the correct XPath query and use the lxmlxpath function like this:

Let’s see what we got exactly:

Congratulations! We have successfully scraped all the data we wanted froma web page using lxml and Requests. We have it stored in memory as twolists. Now we can do all sorts of cool stuff with it: we can analyze itusing Python or we can save it to a file and share it with the world.

Some more cool ideas to think about are modifying this script to iteratethrough the rest of the pages of this example dataset, or rewriting thisapplication to use threads for improved speed.

Once you’ve put together enough web scrapers, you start to feel like you can do it in your sleep. I’ve probably built hundreds of scrapers over the years for my own projects, as well as for clients and students in my web scraping course.

Occasionally though, I find myself referencing documentation or re-reading old code looking for snippets I can reuse. One of the students in my course suggested I put together a “cheat sheet” of commonly used code snippets and patterns for easy reference.

I decided to publish it publicly as well – as an organized set of easy-to-reference notes – in case they’re helpful to others.

While it’s written primarily for people who are new to programming, I also hope that it’ll be helpful to those who already have a background in software or python, but who are looking to learn some web scraping fundamentals and concepts.

Table of Contents:

- Extracting Content from HTML

- Storing Your Data

- More Advanced Topics

Useful Libraries

For the most part, a scraping program deals with making HTTP requests and parsing HTML responses.

I always make sure I have requests and BeautifulSoup installed before I begin a new scraping project. From the command line:

Then, at the top of your .py file, make sure you’ve imported these libraries correctly.

Making Simple Requests

Make a simple GET request (just fetching a page)

Make a POST requests (usually used when sending information to the server like submitting a form)

Pass query arguments aka URL parameters (usually used when making a search query or paging through results)

Inspecting the Response

See what response code the server sent back (useful for detecting 4XX or 5XX errors)

Access the full response as text (get the HTML of the page in a big string)

Look for a specific substring of text within the response

Check the response’s Content Type (see if you got back HTML, JSON, XML, etc)

Extracting Content from HTML

Now that you’ve made your HTTP request and gotten some HTML content, it’s time to parse it so that you can extract the values you’re looking for.

Using Regular Expressions

Using Regular Expressions to look for HTML patterns is famously NOT recommended at all.

However, regular expressions are still useful for finding specific string patterns like prices, email addresses or phone numbers.

Run a regular expression on the response text to look for specific string patterns:

Using BeautifulSoup

Lxml Web Scraping

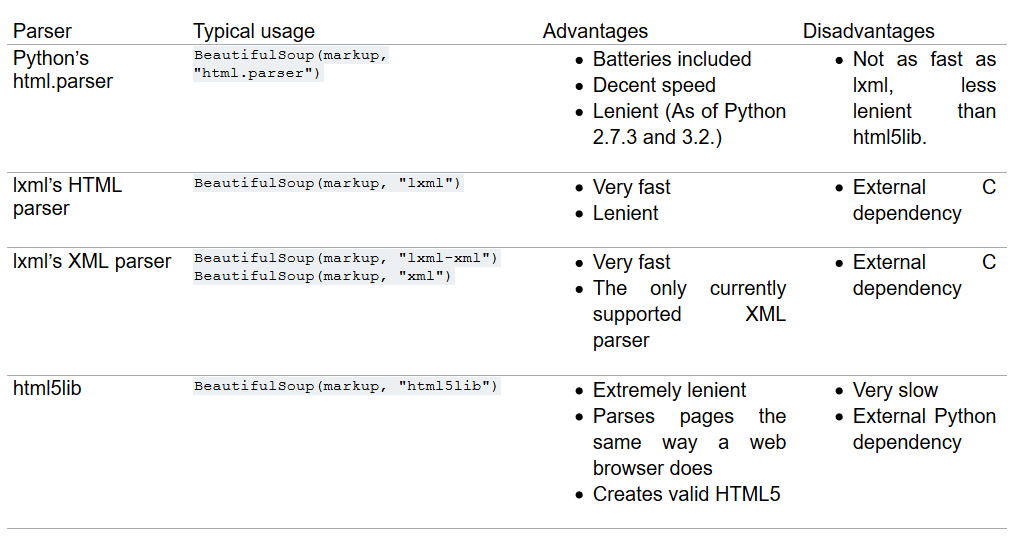

BeautifulSoup is widely used due to its simple API and its powerful extraction capabilities. It has many different parser options that allow it to understand even the most poorly written HTML pages – and the default one works great.

Compared to libraries that offer similar functionality, it’s a pleasure to use. To get started, you’ll have to turn the HTML text that you got in the response into a nested, DOM-like structure that you can traverse and search

Look for all anchor tags on the page (useful if you’re building a crawler and need to find the next pages to visit)

Look for all tags with a specific class attribute (eg <li>...</li>)

Look for the tag with a specific ID attribute (eg: <div>...</div>)

Look for nested patterns of tags (useful for finding generic elements, but only within a specific section of the page)

Look for all tags matching CSS selectors (similar query to the last one, but might be easier to write for someone who knows CSS)

Get a list of strings representing the inner contents of a tag (this includes both the text nodes as well as the text representation of any other nested HTML tags within)

Return only the text contents within this tag, but ignore the text representation of other HTML tags (useful for stripping our pesky <span>, <strong>, <i>, or other inline tags that might show up sometimes)

Convert the text that are extracting from unicode to ascii if you’re having issues printing it to the console or writing it to files

Get the attribute of a tag (useful for grabbing the src attribute of an <img> tag or the href attribute of an <a> tag)

Putting several of these concepts together, here’s a common idiom: iterating over a bunch of container tags and pull out content from each of them

Using XPath Selectors

BeautifulSoup doesn’t currently support XPath selectors, and I’ve found them to be really terse and more of a pain than they’re worth. I haven’t found a pattern I couldn’t parse using the above methods.

If you’re really dedicated to using them for some reason, you can use the lxml library instead of BeautifulSoup, as described here.

Storing Your Data

Now that you’ve extracted your data from the page, it’s time to save it somewhere.

Note: The implication in these examples is that the scraper went out and collected all of the items, and then waited until the very end to iterate over all of them and write them to a spreadsheet or database.

I did this to simplify the code examples. In practice, you’d want to store the values you extract from each page as you go, so that you don’t lose all of your progress if you hit an exception towards the end of your scrape and have to go back and re-scrape every page.

Writing to a CSV

Probably the most basic thing you can do is write your extracted items to a CSV file. By default, each row that is passed to the csv.writer object to be written has to be a python list.

In order for the spreadsheet to make sense and have consistent columns, you need to make sure all of the items that you’ve extracted have their properties in the same order. This isn’t usually a problem if the lists are created consistently.

If you’re extracting lots of properties about each item, sometimes it’s more useful to store the item as a python dict instead of having to remember the order of columns within a row. The csv module has a handy DictWriter that keeps track of which column is for writing which dict key.

Writing to a SQLite Database

You can also use a simple SQL insert if you’d prefer to store your data in a database for later querying and retrieval.

More Advanced Topics

These aren’t really things you’ll need if you’re building a simple, small scale scraper for 90% of websites. But they’re useful tricks to keep up your sleeve.

Javascript Heavy Websites

Contrary to popular belief, you do not need any special tools to scrape websites that load their content via Javascript. In order for the information to get from their server and show up on a page in your browser, that information had to have been returned in an HTTP response somewhere.

It usually means that you won’t be making an HTTP request to the page’s URL that you see at the top of your browser window, but instead you’ll need to find the URL of the AJAX request that’s going on in the background to fetch the data from the server and load it into the page.

There’s not really an easy code snippet I can show here, but if you open the Chrome or Firefox Developer Tools, you can load the page, go to the “Network” tab and then look through the all of the requests that are being sent in the background to find the one that’s returning the data you’re looking for. Start by filtering the requests to only XHR or JS to make this easier.

Once you find the AJAX request that returns the data you’re hoping to scrape, then you can make your scraper send requests to this URL, instead of to the parent page’s URL. If you’re lucky, the response will be encoded with JSON which is even easier to parse than HTML.

Content Inside Iframes

This is another topic that causes a lot of hand wringing for no reason. Sometimes the page you’re trying to scrape doesn’t actually contain the data in its HTML, but instead it loads the data inside an iframe.

Again, it’s just a matter of making the request to the right URL to get the data back that you want. Make a request to the outer page, find the iframe, and then make another HTTP request to the iframe’s src attribute.

Sessions and Cookies

While HTTP is stateless, sometimes you want to use cookies to identify yourself consistently across requests to the site you’re scraping.

The most common example of this is needing to login to a site in order to access protected pages. Without the correct cookies sent, a request to the URL will likely be redirected to a login form or presented with an error response.

However, once you successfully login, a session cookie is set that identifies who you are to the website. As long as future requests send this cookie along, the site knows who you are and what you have access to.

Delays and Backing Off

If you want to be polite and not overwhelm the target site you’re scraping, you can introduce an intentional delay or lag in your scraper to slow it down

Some also recommend adding a backoff that’s proportional to how long the site took to respond to your request. That way if the site gets overwhelmed and starts to slow down, your code will automatically back off.

Spoofing the User Agent

By default, the requests library sets the User-Agent header on each request to something like “python-requests/2.12.4”. You might want to change it to identify your web scraper, perhaps providing a contact email address so that an admin from the target website can reach out if they see you in their logs.

More commonly, this is used to make it appear that the request is coming from a normal web browser, and not a web scraping program.

Using Proxy Servers

Even if you spoof your User Agent, the site you are scraping can still see your IP address, since they have to know where to send the response.

If you’d like to obfuscate where the request is coming from, you can use a proxy server in between you and the target site. The scraped site will see the request coming from that server instead of your actual scraping machine.

If you’d like to make your requests appear to be spread out across many IP addresses, then you’ll need access to many different proxy servers. You can keep track of them in a list and then have your scraping program simply go down the list, picking off the next one for each new request, so that the proxy servers get even rotation.

Setting Timeouts

If you’re experiencing slow connections and would prefer that your scraper moved on to something else, you can specify a timeout on your requests.

Handling Network Errors

Just as you should never trust user input in web applications, you shouldn’t trust the network to behave well on large web scraping projects. Eventually you’ll hit closed connections, SSL errors or other intermittent failures.

Learn More

If you’d like to learn more about web scraping, I currently have an ebook and online course that I offer, as well as a free sandbox website that’s designed to be easy for beginners to scrape.

You can also subscribe to my blog to get emailed when I release new articles.